“But I wouldn’t put anything past this guy because it looks like he’s tremendously exceptional at what he does.”

Predecessors indicate basketball skills — stamina, explosiveness, range, ability to change direction in a blink — translate to the gridiron.

In discussing the merits of James as a football player, an obvious barometer is San Diego Chargers tight end Antonio Gates, a Pro Bowler the past five seasons. Gates originally signed with Michigan State to play both sports, but eventually transferred and played just basketball at Eastern Michigan and Kent State.

“I think LeBron could come in and do better than Antonio Gates,” New England Patriots receiver Randy Moss said. “LeBron James is the athlete that comes around every so often.

“He’s at a point in his career where the things that he does are something we haven’t seen before. … It’s just very rare for athletes to be able to do the things that he does to entertain and wow us night in and night out.”

The Jets last month signed Cleveland State power forward J’Nathan Bullock to play tight end, even though he hadn’t worn a helmet since high school.

“From my perspective, the best athletes in the world play in the NBA,” University of Akron football coach J.D. Brookhart said. “Look at what Gates did. He was a pretty good basketball player athletically, but LeBron’s world class.”

Brookhart is known as one of the country’s best receivers coaches. His previous gig was at the University of Pittsburgh, where he worked with Larry Fitzgerald and Antonio Bryant. One of his first roster decisions at Akron was switching another future NFLer, Domenik Hixon, from safety to receiver.

“It’s not very hard to tell at all how good of a football player LeBron would be,” Brookhart said. “Had he pursued it, I think he’d be an All-Pro receiver.

“With that body and skills that he has, I think even if he wasn’t a 4.4 or 4.5 speed guy — and I’m not so certain he wouldn’t be that — he would pose absolutely unwinnable matchups out there.”

Patriots defensive coordinator Dean Pees has been aware of James’ football skills for years and knows plenty about Gates.

Pees recruited Gates to play linebacker at Michigan State and was head coach at Kent State when Gates was there. Kent is 17 miles from St. Vincent-St. Mary.

“You look at it and you’d have to say, having seen Tony Gonzalez and seen Antonio Gates, that the guy definitely could have played,” Pees said of James. “He was a phenomenal athlete. If he wanted to play football, he certainly could’ve.”

A switch to the gridiron, however, would be no slam dunk.

There would be questions about his open-field speed.

“A lot of those basketball players, they can’t run,” Parcells said. “They don’t have legitimate speed. This kid’s pretty amazing, though.”

There would be questions about his ability to withstand violent collisions.

“How bad is a 5-10, 180-pound corner going to hurt that body?” Brookhart asked.

Without ever having held a stopwatch on him, Pees guessed James would not possess receiver wheels. That, combined with James’ body type, would make him a tight end who’d be considerably more vulnerable to contact than a wideout.

“The biggest thing he wouldn’t be ready for is somebody hitting him,” Pees said. “I know they play physical in the NBA, so put [former Patriots outside linebacker] Adalius Thomas up in his face all day and have a defensive back maybe behind him that has some size too, that can go up with him.

“You could never put a little guy on him. They’d just lob the ball, and nobody could defend him. You’d have to hit him at the line. I would think you’d want a big guy that could hit him at the line and see how much he could take.”

Jets vice president of college scouting Joey Clinkscales, a former NFL receiver, agreed with Pees that James probably would make a better tight end than a wideout.

But Clinkscales wasn’t nearly as concerned about James’ ability to withstand football’s physical demands.

“The only reservation I think you’d have is the constant day-to-day beatings that he would take,” Clinkscales said. “You don’t know about the blocking ability, but athletically he could flex out. And the physical nature of the player, he’s just such a naturally big and muscular guy.

“He would have a chance to be as good as anybody playing right now.”

There also would be questions about whether a pop-culture icon who generates about $40 million a year would be committed enough to accept an enormous pay cut.

Clubs would be more willing to take a chance on an unproven-yet-intriguing specimen if he didn’t command a huge financial commitment. Gates wasn’t drafted. The Chargers’ risk was trifling.

“You’re willing to take a chance on those guys because there’s no cost factor involved,” Pees said. “There’s no risk. If it doesn’t work out, fine. If it does work out, it’s a big-time story. How would you draw up a contract for LeBron James?

“You can’t throw starting tight end money at a guy that has never played and might not work out. At the same time, it’s LeBron James. That’d be a really tough one.”

The temptation might be too much for some clubs.

James’ raw potential and star power make him attractive to personnel men and marketers alike. Teams would be afraid that James would sign with a division rival.

“Can you pass on a guy that potentially can be a difference-maker at his position?” Clinkscales asked. “You wouldn’t know that from day one, but some of the athletic skills will make you say ‘Wow.’ You don’t know for sure, but you have a pretty good idea.

“I think there would be a bit of a bidding war.”

The fanciful notion of James testing the NFL is significantly less ridiculous than his idol, Michael Jordan, trying to play baseball. At least with James, tangible football evidence exists.

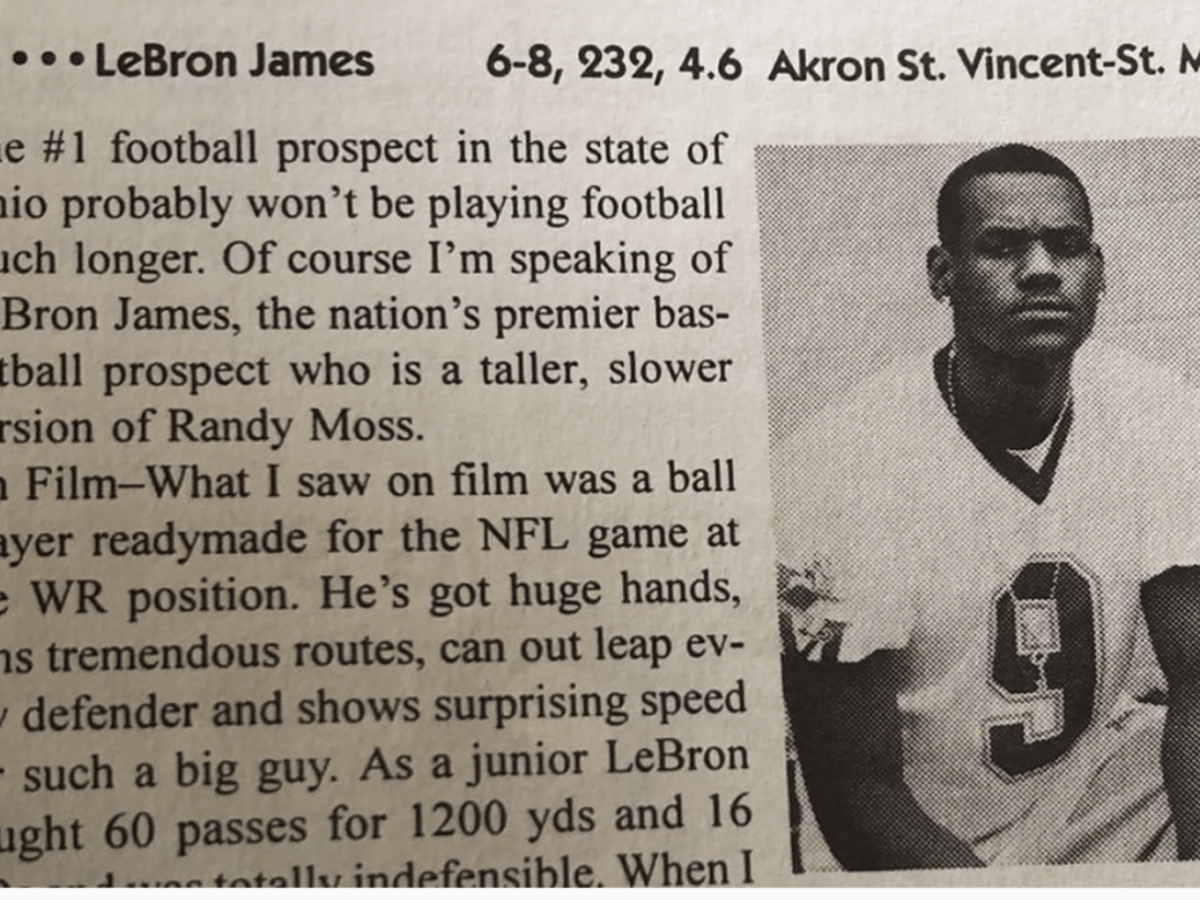

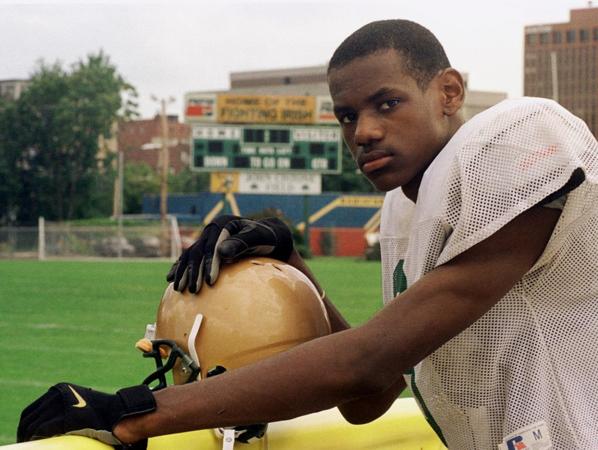

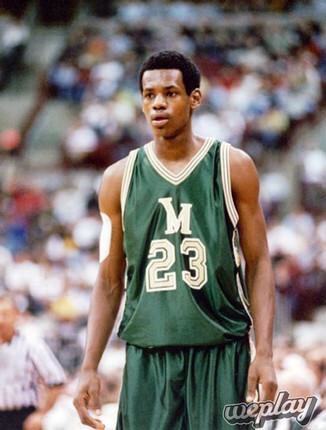

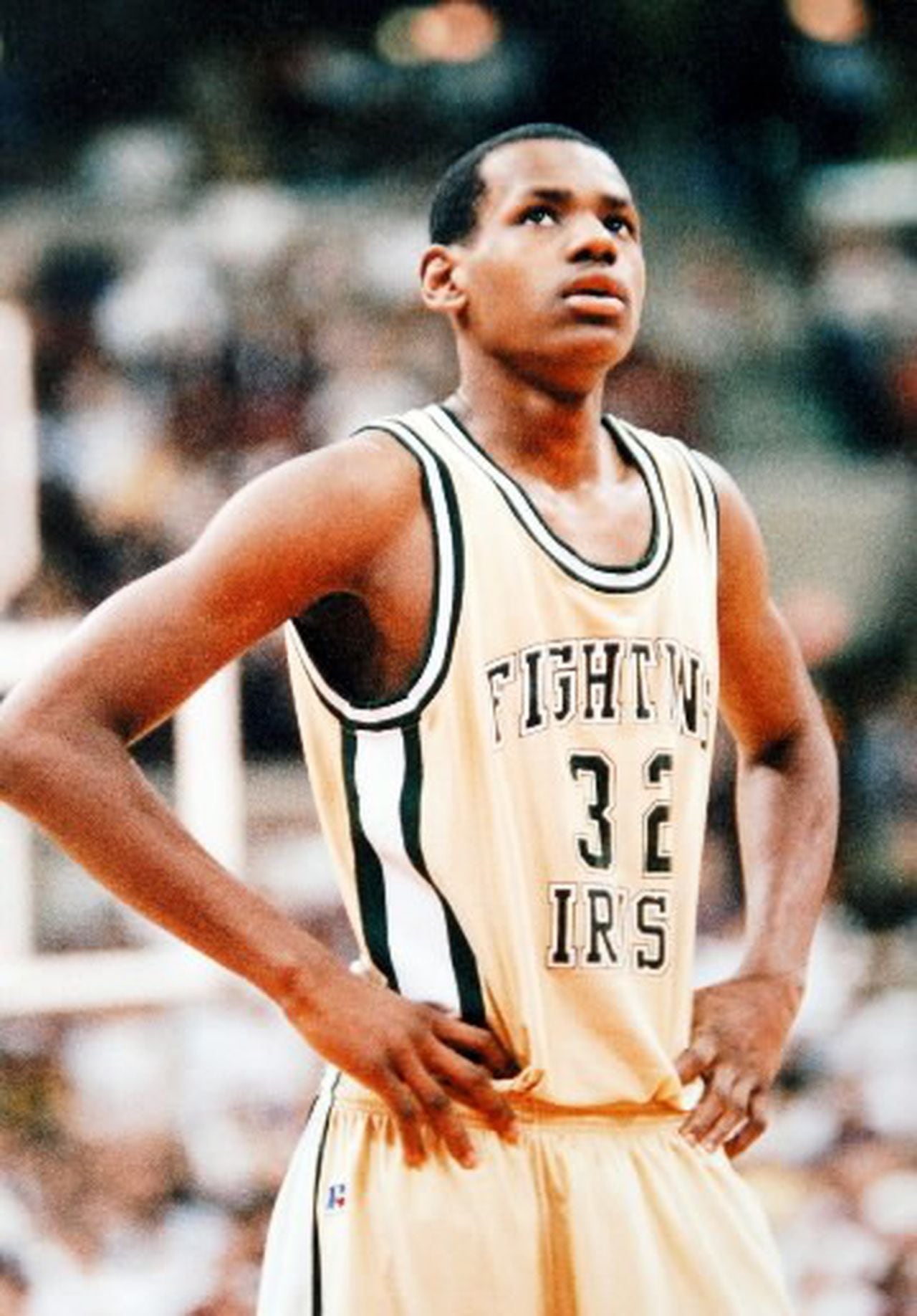

James was a good enough receiver at St. Vincent-St. Mary that it’s believed he could have commanded a football scholarship to the program of his choice after his sophomore season. He was being monitored by Ohio State and Notre Dame.

He played only two full seasons of varsity football, but he made his mark. His first varsity start came as a freshman in the state playoffs. He caught nine passes, a school record.

James’ name still is scattered throughout the St. Vincent-St. Mary football record book.

He grabbed 42 passes for 752 yards and 11 touchdowns as a 6-6 sophomore, but his budding basketball fame soon curbed the excitement of football recruiters.

“About three games into his sophomore year, we knew he was done, that he would never go to college,” said James’ high school basketball coach, Keith Dambrot, now the head coach at Akron. “When you know you’re not going to college and you’re a surefire pro, then you’ve got to start making business decisions.”

While his football teammates were going through preseason drills and scrimmages the summer before his junior year, James was in Chicago for a private workout with Jordan, Antoine Walker, Jerry Stackhouse and Penny Hardaway.

James was torn about playing football again. He loved the sport, but he didn’t want to jeopardize his incandescent future.

“It was a sacrifice because he’ll tell you he liked Friday night football better than anything,” Dambrot said. “He liked basketball practice better than football practice, but he loved Friday night football.”

James was on the sideline for St. Vincent-St. Mary’s season opener, an upset victory over Akron Garfield. Watching in street clothes was like torture. The next night, 22-year-old singer Aaliyah died in a plane crash.

Those two moments sent James into a deep introspection about his future. He discussed the situation with his mother, Gloria, who didn’t want him to play football. They came to the realization bright futures don’t come with guarantees.

He made up his mind that weekend to wear cleats again.

“I’m just 16, and you’re only in high school once,” James told the Akron Beacon Journal.

Murphy recalled a particular moment from James’ junior year that illustrated his passion for football. James made a one-handed grab for a 7-yard touchdown against Villa Angela-St. Joseph in the waning moments of the first half. James absorbed a hit on the play and broke the index finger on his left hand.

“He was pretty shook up at halftime,” Murphy said. “He was thinking about basketball and what this was going to do. Once the trainers got him calmed down, we said ‘Look, LeBron. You don’t even have to play in the second half. Or we can use you as a decoy and we’ll throw to the other guys if you want.'”

As the team filed out of the locker room, James turned to the coaches, three of whom had played in the NFL — head coach Jay Brophy, assistant Frank Stams and Murphy.

“I’m no decoy,” James told them.

“The guy loves to compete,” Murphy said. “He loves to play. He loves football.”

James finished his junior season with 57 receptions for 1,160 yards and 16 touchdowns, propelling St. Vincent-St. Mary to the state semifinals. James also played prevent safety and often quarterbacked the scout team. Murphy said James could throw a football 70 yards.

“The physical tools were overwhelming,” Scouts Inc. analyst Matt Williamson said. Williamson was a recruiter for Pitt and followed Brookhart to Akron as football operations director before joining the Cleveland Browns’ scouting department. “He really stood out. He made you think ‘Wow.’ But you don’t get too enamored because you know he’s the best basketball player in the world.”

Pees took a similar approach with James. It was foolish to waste precious recruiting time on an emerging basketball enterprise.

“If he went to Akron, their football program would have been top 20,” said St. Vincent-St. Mary grad Chip Hilling, who saw almost all of James’ games. Hilling played linebacker at Indiana University for head coaches Lee Corso, Sam Wyche and Bill Mallory. “He really was an incredible football player.

“With LeBron’s athleticism, I could see him as a tight end, H-back, receiver. LeBron could wreak havoc as an outside linebacker, edge pass rusher. He’s a freak.”

NFL media guides, of course, are loaded with bios of special-teamers, journeymen and practice-squad players who were all-everythings in high school. And they benefited from college training.

Even so, James might be able to pull off the basketball-to-football transformation.

If he wanted to enter the NFL, he wouldn’t have to declare for the draft. He’d be free to sign with any team.

“It wouldn’t surprise me at all if, after one phone call, he didn’t have six or seven suitors after him,” Clinkscales said.

Parcells, Pees and Williamson were hesitant to project greatness. Each of them chuckled at the idea of James giving football a shot, but none discounted the possibility he would make it work.

“He has size and athletic ability, so I’m certain you’d investigate things that he could do,” Parcells said. “That would take a little thought.”

Brookhart, though, estimated it would take less than three years to complete the conversion from all-world hoospter to all-world receiver.

“He’d be dang successful pretty quick, by the midpoint of his first season,” Brookhart said. “But between Year 2 or 3 is when you would see him rise to another level.”

That’s considered the timetable for a young receiver to make the mental adjustment from college to the NFL. They need to learn the system until it’s in their subconscious, and they can identify defenses and recognize coverages.

“There’s a lot of post-snap adjustments you have to be able to make,” Brookhart said. “Those take repetition, repetition, repetition and a lot of different looks to the point the game actually slows down. You’re not thinking.”

Murphy is in agreement based on what he witnessed with eyes that have glimpsed the best.

If Murphy ranks James fourth behind only Lofton, Rice and Largent, then he’s ranking James ahead of former teammates Sterling Sharpe and John Jefferson, NFC contemporaries such as Art Monk, Henry Ellard and Anthony Carter and so many others he has competed against.

“I went against Lofton every day in practice,” Murphy said. “I saw all the things that he did. I saw his abilities and his running and his burst and his catching ability. It was the same thing to see the plays that Jerry Rice made and what he brought to the game.

“I was coaching LeBron in high school and I’m seeing him make plays that made me say ‘Lofton did that. Rice did that.’

“He’s scary. He really was a scary player.”

AFC East blogger Tim Graham covers the NFL for ESPN.com.